CWS TRIPOD

The Lord's Supper

|

||

|

|

|

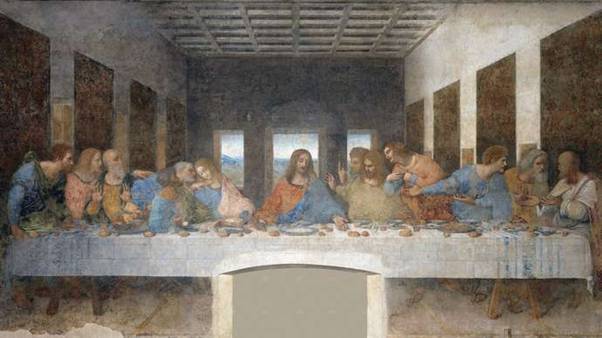

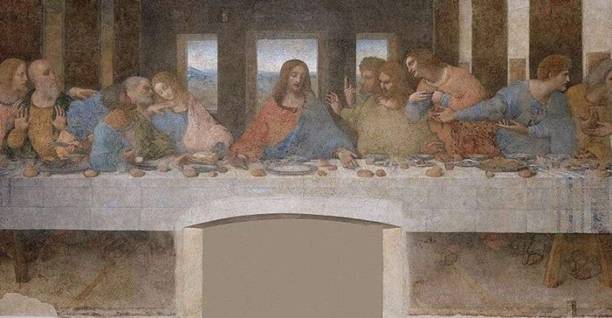

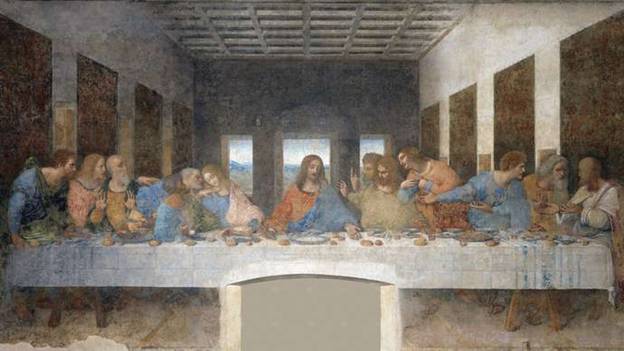

Leonardo da Vinci - The Last Supper The Last Supper - 1498 Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie - Milan - Italy

For centuries this spectacular mural has been seen as one of the world's finest paintings and perhaps the greatest expression of its creator, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), who played a leading role at the forfront of the Italian Renaissance - the flourishing of the learning that peaked in the sixteenth century. His genius lay in an inventive curiosity that embraced both art and sciences. The Last Supper is the perfect synthesis of Leonardo's talent. Cleverly situated and conceived, it looks down from its lofty position on the north wall of the Convent of Santa Maria's refectory. As the diners sat down to eat, Christ and his twelve disciples cast their inspiring spiritual presence over the pious individuals beneath, Leonardo subtly highlights Christ's status in the group by painting his figure slightly larger and framed against the light of the window. He introduces human drama to the mural by choosing to illustrate the point when the disciples ask Christ who would betray him. Each disciple is shown reacting in a way that reveals much about them without resorting to the symbolism forced by his contemporaries. Da Vinci painted this mural on a dry plaster, which allowed him to work it as a whole, rather than having to finish one section at a time as was norm with traditional wet-plaster frescoes. Sadly, decay set in early because medium was less durable. Two early copies of The Last Supper are known to exist, presumably the work of Leonardo's assistant. The copies are almost the size of the original, and have survived with a wealth of original detail still intact. This bold experimentation, along with his pioneering grasp of composition, light, and perspective, are among the reasons da Vinci achieved an eminence that has lasted across centuries.

About the significance of the attitude and position of the Apostles: From left to right: Bartholomew, James, son of Alphaeus and Andrew form a group of three, all are surprised. Judas Iscariot, Peter and John form another group of three. Judas is wearing green and blue and is in shadow, looking rather withdrawn and taken aback by the sudden revelation of his plan. He is clutching a small bag, perhaps signifying the silver given to him as payment to betray Jesus, or perhaps a reference to his role within the 12 disciples as treasurer. He is the only person to have his elbow on the table and his head is also horizontally the lowest of anyone in the painting. Peter looks angry and is holding a knife pointed away from Christ, perhaps foreshadowing his violent reaction in Gethsemane during Jesus' arrest. The youngest apostle, John, appears to swoon. Jesus Apostle Thomas, James the Greater and Philip are the next group of three. Thomas is clearly upset; James the Greater looks stunned, with his arms in the air. Meanwhile, Philip appears to be requesting some explanation.

Matthew, Jude

Thaddeus and Simon

the Zealot are

the final group of three. Both Jude Thaddeus and Matthew are turned

toward Simon, perhaps to find out if he has any answer to their initial

questions. Last Supper fresco by Leonardo da Vinci Print Cite Share More WRITTEN BY Alicja Zelazko is the Assistant Editor, Arts and Humanities, covering topics in the visual arts, architecture, music, and performance. Before joining Encyclopædia Britannica in 2017, she worked at the... Alternative Title: “Cenacolo” Last Supper, Italian Cenacolo, one of the most famous artworks in the world, painted by Leonardo da Vinci probably between 1495 and 1498 for the Dominican monastery Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. It depicts the dramatic scene described in several closely connected moments in the Gospels, including Matthew 26:21–28, in which Jesus declares that one of the Apostles will betray him and later institutes the Eucharist. According to Leonardo’s belief that posture, gesture, and expression should manifest the “notions of the mind,” each one of the 12 disciples reacts in a manner that Leonardo considered fit for that man’s personality. The result is a complex study of varied human emotion, rendered in a deceptively simple composition.

Leonardo da Vinci: Last Supper Last Supper, wall painting by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1495–98, after the restoration completed in 1999; in Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Images Group/REX/Shutterstock.com

Subject The subject of the Last Supper was a popular choice for the refectory walls of monasteries and convents in 15th-century Italy, whereby nuns and monks could have their meals in the presence of Jesus’ final repast. Leonardo’s version appears neatly arranged, with Jesus at the centre of an extensive table and the Apostles to his left and right. He wears the traditional red and blue robes and has a beard, but Leonardo did not imbue him with the customary halo. Some scholars have proposed that the light from the window behind him serves this role or that the implied lines of the pediment above the window create the illusion of a halo. Other scholars have argued that the missing attribute may also suggest that Jesus is still a human being, who, as such, will endure the pain and suffering of the Passion. The scene is not a frozen moment but rather a representation of successive moments. Jesus has declared his forthcoming betrayal, and the Apostles react. Philip, who stands in the group to Jesus’ left, gestures toward himself and seems to say, “Surely not I, Lord?” Jesus seems to reply, “The one who has dipped his hand into the bowl with me will betray me” (Matthew 26:23). Simultaneously, Jesus and Judas, who sits with the group to Jesus’ right, reach toward the same dish on the table between them, an act that marks Judas as the betrayer. Jesus also gestures toward a glass of wine and a piece of bread, suggesting the establishment of the Holy Communion rite.

Jesus’ serene composure, with his head and eyes lowered, contrasts with the agitation of the Apostles. Their varying postures rise, fall, extend, and intertwine while remaining organized in groups of three. James the Greater, to Christ’s left, throws his arms out angrily while the disbelieving Thomas, crouched behind James, points upward and seems to ask, “Is this God’s plan?” His gesture anticipates his later reunion with the resurrected Christ, a moment that was often represented in art with Thomas using his fingers to touch Christ’s wounds from the crucifixion to quell his doubts. Peter, who is identified by the knife in his hand that he will later use to sever the ear of a soldier attempting to arrest Jesus, moves toward the mild-tempered John, who sits to Jesus’ right and appears to swoon. Judas, gripping the purse that contains his reward for identifying Jesus, recoils from Peter, seemingly alarmed at the other Apostle’s quick action.The rest of the Apostles appear to whisper, grieve, and debate among themselves. The meal takes place within an almost austere room so that the viewer focuses on the action taking place in the foreground. Dark tapestries line the walls on either side, while the back wall is dominated by three windows that look out on an undulating landscape recalling Milan’s countryside. Leonardo represented the space by using linear perspective, a technique rediscovered in the Renaissance that employs parallel lines that converge at a single vanishing point to create the illusion of depth on a flat surface. He placed the vanishing point at Jesus’s right temple, thus drawing the viewer’s attention toward the main subject. Although linear perspective seems like a systemized method of creating the illusion of space, it is complicated by its reliance on a single vantage point. Any viewing position other than the vantage point reveals a slightly distorted painted space. Later, scholars discovered that the vantage point for the Last Supper is about 15 feet (4.57 metres) above ground. Leonardo likely chose this relatively high height because the painting’s bottom edge is 8 feet (2.44 metres) above ground and using a vantage from the floor would have meant viewers would only have been able to see the underside of the table, not the action taking place above. Consequently, the painted space of the Last Supper always appears sightly at odds with the refectory space. It is one of many visual paradoxes scholars have observed about the painting. They have also noted that the table is far too large to fit in the depicted room, yet it is not large enough to seat the 13 men, at least not along the three sides where they are placed. The scene, so seemingly simple and organized, is a puzzling resolution to the challenge of creating the illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat surface. History The wall painting was commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, the duke of Milan and Leonardo’s patron during his first extended stay in that city. The Sforza coats of arms appear with the family’s initials on the three lunettes above the mural. Leonardo likely began working on the painting in 1495 and, as was his manner, worked slowly with long pauses between sessions, until he finished in 1498. Because of Leonardo’s notorious perfectionism, true fresco painting was not ideal, as the process requires that an artist apply paint quickly to each day’s fresh plaster before the plaster dries and bonds the pigment to the wall. Instead, Leonardo tried an experimental technique using tempera or oil paint on two layers of dry preparatory ground. His compromised process meant that the pigments were not permanently attached to the wall, however, and the painting began to flake within a few years. It continued to deteriorate, suffering from the steam and smoke of the monastery’s kitchen, soot from the refectory’s candles, and the dampness of the location. In the ensuing centuries, the painting sustained additional damage. In 1652 a door was cut into the north wall, removing Jesus’ feet and loosening the paint and plaster. Several restorations followed, with heavy-handed retouches and the application of varnish, glue, solvents, and the like. The painting endured additional irreverence when Napoleon’s invading troops used the refectory as a stable. After a flood in the beginning of the 19th century, mold growth damaged the painting further still. During World War II the painting suffered its greatest catastrophe, when an Allied bomb caused the roof and one wall of the refectory to collapse. The painting survived, but it was exposed to the elements for several months before the space was rebuilt. After centuries of maltreatment, the Last Supper underwent an extensive and controversial 20-year restoration that was completed in 1999. Restorers worked in small sections to remove previous retouches, layers of grime, and coats of varnish while adding beige watercolour to the parts that could not be recovered. When the restored painting was revealed, many critics argued that the restorers had removed so much of the painting that very little was left of Leonardo’s original work. Others, however, commended the recovery of such details as the Apostles’ expressions and the food on the table. Legacy The painting, despite restoration efforts, remains fragile, so, in an effort to slow its deterioration, visitors are allotted 15 minutes to view the mural in small groups. Although some of Leonardo’s celebrated artistic qualities—luminous colour, soft modeling, and studied facial expressions—have been lost, viewers can still witness his skill in depicting a sequential narrative, his considered approach to creating an illusion of space, and his interest in representing human psychology in expression, gesture, and posture. Since the Last Supper’s completion, when it was declared a masterpiece, the mural has garnered the praise of such artists as Rembrandt van Rijn and Peter Paul Rubens and such writers as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. It has also inspired countless reproductions, interpretations, conspiracy theories, and works of fiction. The Last Supper’s delicate condition has not lessened the painting’s appeal; instead, it has become part of the artwork’s legacy.

The Guy Who Cut the Door into The Last Supper May 14, 2019 4 8,300 1 minute read

If you’ve ever been to Milan, Italy and seen Leonardo da Vinci’s memorable painting “The Last Supper,” one of the first things you notice is that there’s a door cut right into the painting. That wasn’t Leonardo’s original plan, and it cuts into a significant part of the masterpiece. Art historians believe it happened in the 17th century, and don’t know who actually did it. But this much we know: The guy didn’t have much vision. Back then, the painting wasn’t appreciated as much as it is today, and had already gone through multiple attempts at restoration. But even then, cutting a door through it was an incredibly stupid idea. But it happened because the people involved were more practical that artistic. They weren’t thinking about the bigger picture. (See what I did there?) I assume somebody needed to get into the next room, but instead of discussing all the possible options, they simply took the most direct route – right through the middle of the masterpiece. The lesson? While the practical way may seem expedient, cheap, and efficient, stop and think about the long term impact. It happens in organizations every day. Have you been asked to cut a door through a masterpiece? In your case, it may not be a priceless painting, but we’re all regularly torn between doing the

Cheap thing But sometimes we have to do the brave thing. Sometimes the brave thing takes real courage. Before you make your decision, remember The Last Supper” and always choose the brave thing. Leonardo da Vinci Made a Secret Copy of ‘The Last Supper’ and, Miraculously, It Still Exists A new documentary tracks down the second version of Leonardo's masterpiece. Sarah Cascone, March 20, 2018

The Tongerlo Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci and his studio. Courtesy of the Sheen Center. Turns out The Last Supper had a second course. A near-pristine copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic painting—created by the Renaissance master and his studio—is offering a glimpse into what one of the world’s most famous artworks looked like when it was new. The Last Supper is simultaneously one of art history’s greatest triumphs and biggest tragedies: The towering artist captured the emotional and dramatic intensity of one of the most important episodes from the Gospels, but he was so committed to outdoing the typical cenacolo fresco that he chose an untested medium, using oil paint that failed to bind with the underlying plaster and began decaying within years of its initial application. The centuries have not been kind to the masterpiece—only 20 percent of the original painting is thought to remain intact, making it difficult to fully comprehend the impact the piece would have had when it was new. But what if there was a way to turn back time, to return to Leonardo’s studio, if you will, and see The Last Supper as he did? When authors Jean-Pierre Isbouts and Christopher Heath Brown were working on their 2017 book The Young Leonardo: The Evolution of a Revolutionary Artist, 1472–1499, which follows the Renaissance great from his career beginnings in Florence to his major breakthrough, The Last Supper, they assumed such a miracle was impossible. Then, one day at a party, a friend told them that there was a second version of the painting, completed by Leonardo and his studio on canvas just a few years after the original mural. “I said ‘you’re crazy!'” Brown told artnet News at a recent screening of the pair’s new documentary short, The Search for the Last Supper, at New York’s Sheen Center for Thought and Culture. The film tracks the origins of this little-known second version and the authors’ efforts to trace it to a remote abbey in Tongerlo, Belgium, an hour outside Antwerp.

Young Leonardo: The Evolution of a Revolutionary Artist, 1472–1499 by Jean-Pierre Isbouts and Christopher Heath Brown (2017). Courtesy of Thomas Dunne Books / St. Martin’s Press. When they finally found the second painting, they were amazed to discover just how good the Tongerlo Last Supper looked. The figures line up perfectly, suggesting it was made using the same cartoons used to produce the original. “When we went to overlay them, we had no idea they were going to be such a perfect match,” said Isbouts. The film shows how the work on canvas fills in the gaps in the famed fresco, seemingly completing the painting. The completion of The Last Supper marked the end of the first stage of Leonardo’s career, the fulfillment of his early promise in the form of a painting immediately recognized for its artistic genius. Among the work’s early admirers, in fact, was King Louis XII of France, who had conquered Milan, and, according to art historian Giorgio Vasari, had taken the time to visit Santa Maria della Grazie. The king desperately hoped to bring the painting with him to France, which was then severely lacking in arts and culture, “but the fact that it was painted on a wall robbed his Majesty of his desire, and so the picture remained with the Milanese,” wrote Vasari. According to Brown and Isbouts, the king was nevertheless undeterred. “If he can’t have the fresco itself, he will have the next best thing: a copy on canvas, that he can take back to France,” the documentary explains. The film points to a letter dated to January 1507, tracked down in the archives in Florence, in which the king writes that “we have need of Leonardo da Vinci,” who had an assignment back in his native city. Based on this evidence, it seems likely that Louis XII commissioned Leonardo and his studio to paint a full-scale copy of The Last Supper, just eight years after they completed the original in 1499. Furthermore, a 1540 inventory of the governor of Milan’s estate in Gaillon, France, includes a “Last Supper on canvas with monumental figures that the king brought over from Milan.”

The poster for The Search for the Last Supper. Courtesy of the Sheen Center. Brown and Isbouts believe that Andrea Solario, one of Leonardo’s best assistants, was largely responsible for overseeing the work, as he was with other known copies of the artist’s work created by his studio. Solario is known to have been in Milan while Leonardo was completing the original version of The Last Supper, and worked at the Gallion estate beginning in 1507—presumably arriving with the completed copy. The work was then purchased in 1545 by the abbey in Tongerlo, Belgium—perhaps, the documentary argues, in defiance of Calvinist prohibitions against religious art. At the time, the abbot identified the work as a Leonardo. Today, Brown and Isbouts have shown the painting to experts who believe some 90 percent of it was done by members of the artist’s studio. The paintings of Jesus Christ and St. John, however, may be by Leonardo himself—unlike the rest of the painting, X-ray analysis shows no underdrawings for these two important figures. Seeing the long-forgotten copy for the first time “was overwhelming. I was blown away—it’s so vast,” Isbouts said. “The fresco is the fresco and that’s the original painting—but there’s so little you can see! So you need to see Milan, and then you need to see the Tongerlo.” Leonardo’s studio also produced a third copy in about 1520, led by Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, or Giampietrino, that now belongs to London’s Royal Academy, but it is not as faithful a replica. “Although it is a copy, it was seen as a real window into the achievements of Milan,” and an educational tool for students, the documentary notes. (Because of renovations to the academy, it is currently hung high on the wall of the Magdalen Chapel at Oxford.) The documentary, which will air on local PBS stations, aims to inform viewers about the little-known Tongerlo copy and its fidelity to the now-nearly ruined original, but also to help raise funds for the much-needed restoration of the canvas. While it is in good shape compared to the ravaged mural, it endured significant damage during a fire at the abbey in 1929. “It’s made up of multiple canvases stitched together, and they’re very very delicate,” said Isbouts, who expects the full restoration will cost €500,000 ($616,000). “All the funds will be wired directly to the account of the abbey, who are delighted.” Watch the trailer for the documentary:

Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci Leonardo’s Last Supper (1495–98) is among the most famous paintings in the world. In its monumental simplicity, the composition of the scene is masterful; the power of its effect comes from the striking contrast in the attitudes of the 12 disciples as counterposed to Christ. Leonardo portrayed a moment of high tension when, surrounded by the Apostles as they share Passover, Jesus says, “One of you will betray me.” All the Apostles—as human beings who do not understand what is about to occur—are agitated, whereas Christ alone, conscious of his divine mission, sits in lonely, transfigured serenity. Only one other being shares the secret knowledge: Judas, who is both part of and yet excluded from the movement of his companions. In this isolation he becomes the second lonely figure—the guilty one—of the company. Leonardo da Vinci: Last Supper Last Supper, wall painting by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1495–98, after the restoration completed in 1999; in Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Images Group/REX/Shutterstock.com Leonardo da Vinci: Last Supper Last Supper, wall painting by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1495–98, before the restoration completed in 1999; in Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. SuperStock In the profound conception of his theme, in the perfect yet seemingly simple arrangement of the individuals, in the temperaments of the Apostles highlighted by gesture, facial expressions, and poses, in the drama and at the same time the sublimity of the treatment, Leonardo attained a height of expression that has remained a model of its kind. Countless painters in succeeding generations, among them great masters such as Rubens and Rembrandt, marveled at Leonardo’s composition and were influenced by it and by the painting’s narrative quality. The work also inspired some of Goethe’s finest pages of descriptive prose. It has become widely known through countless reproductions and prints, the most important being that produced by Raffaello Morghen in 1800. Thus, Last Supper has become part of humanity’s common heritage and remains today one of the world’s outstanding paintings. Technical deficiencies in the execution of the work have not lessened its fame. Leonardo was uncertain about the technique he should use. He bypassed traditional fresco painting, which, because it is executed on fresh plaster, demands quick and uninterrupted painting, in favour of another technique he had developed: tempera on a base, which he mixed himself, on the stone wall. This procedure proved unsuccessful, inasmuch as the base soon began to loosen from the wall. Damage appeared by the beginning of the 16th century, and deterioration soon set in. By the middle of the century, the work was called a ruin. Later, inadequate attempts at restoration only aggravated the situation, and not until the most-modern restoration techniques were applied after World War II was the process of decay halted. A major restoration campaign begun in 1980 and completed in 1999 restored the work to brilliance but also revealed that very little of the original paint remains.

|

|

A Summary and Analysis of the Last Supper By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University) The Last Supper is the meal that Jesus shares with his disciples after his triumphant entry into Jerusalem. At the Last Supper, Jesus announces that one of his disciples will betray him. The meal is the subject of one of the greatest works of Renaissance art, a mural painted on the wall of a nun’s refectory by Leonardo da Vinci; it is also, of course, the origins of the ceremony known as the Eucharist, in which bread and wine are taken in memory of Jesus’ body and blood. 0 seconds of 15 secondsVolume 0%

But the phrase ‘Last Supper’ appears nowhere in the Bible, and our perception of this event is, in most cases, wrong. Let’s take a closer look at the event known as the ‘Last Supper’, by analysing what the Bible actually tells us. The Last Supper: summary All four of the Gospels describe the Last Supper; below we follow the story of the Last Supper as it’s set out in the Gospel of Matthew 26:17-30, with occasional embellishments from the other gospels. The Last Supper takes place during the Jewish festival of Passover. Jesus announced that he would keep the Passover with his twelve disciples. (In the Gospel of Mark 14:13-15, Jesus specifically directs his disciples to a man in the city who will show them an upstairs guest-room all ‘furnished and prepared’ for them to eat their Passover meal together.) When evening came, Jesus sat and ate with his disciples. He told them that one of them would soon betray him. They were all saddened by this, and asked Jesus in turn, ‘Is it I?’ But Jesus would only say that it was one of the men who dipped his hand with Jesus in the food dish. Judas, who betrayed Jesus, asked Jesus, ‘Master, is it I?’ But all Jesus said in response was, ‘Thou hast said.’ Jesus took some bread and blessed it, breaking it and giving each of his disciples a piece. He told them to take it and eat for ‘this is my body.’ He then took the cup of wine, blessed it, and gave the wine to them, telling them to drink it because ‘this is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many for the remission of sins.’ Jesus added that he would not drink wine again after this, until he drank it in heaven with his disciples when they were all reunited in God’s kingdom. In Luke’s gospel, Jesus also told Peter that before the cock crowed that day, Peter would deny knowing Jesus, three times (Luke 22:34). After supper they all sang a hymn and then went out to the mount of Olives. Shortly after this, Judas betrayed Jesus by publicly identifying him (by greeting him with a kiss) so the officials knew whom to arrest.

The Last Supper: analysis The Last Supper is an important event in the history of Christianity because it immediately precedes Jesus’ betrayal and subsequent arrest. It is also of significance because of Jesus’ identification of the bread and wine as symbolic of his own body and blood. They have been eaten and drunk in memory of him, and his sacrifice, ever since. But whether Jesus meant that the bread and wine, when taken at Holy Communion, merely to symbolise his body and blood, or whether he meant that they would somehow, through God’s divine presence, become transformed through the sacrament into his body and blood, is something that Christians – notably Protestants and Catholics – have disagreed over. Indeed, during the Reformation of the sixteenth century, denying transubstantiation – that is, the doctrine which stated that the bread and wine at Communion literally became Jesus’ body and blood – could get you burnt at the stake. However, Jesus often speaks in metaphors and so stating ‘this is my body’ and ‘this is my blood’ needn’t mean that his words should be taken literally. The phrase ‘Last Supper’ emerged later than the accounts of this meal given in the Bible. Even now, though, some Christians – particular Protestants – avoid using the term, preferring to speak of the ‘Lord’s Supper’ on the grounds that the meal we commonly know as the ‘last’ supper probably wasn’t the very last meal Jesus ate with the apostles. Here’s a question for you: in which book of the New Testament do we find the earliest reference to the Last Supper? Not in any of the four Gospels – although they all describe this meal – but in St Paul’s 1st Epistle to the Corinthians, which was (almost certainly) written before any of the four Gospels. In 1 Corinthians 23-27, Paul sets out the relationship between the Last Supper and Holy Communion – the importance of the bread and wine – although he doesn’t describe the meal in detail, other than saying Jesus ‘took bread’ on ‘the same night in which he was betrayed’. The question of how the disciples ate at the Last Supper is also not as straightforward as we might first think. Although Luke tells us that Jesus ‘sat down’ with his disciples to eat, in John 13:23 we are told ‘there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.’ This disciple is usually identified with John himself, and this is the interpretation Leonardo da Vinci followed in his famous painting of the Last Supper. But why was he ‘leaning on Jesus’ bosom’? Were they sitting down at all? It’s been pointed out that in Roman-occupied Palestine, the custom was to lie on one’s front and dine in this position, rather than sitting on chairs. Not only this, but it was Jewish custom at meals, and especially at Passover, to recline around a low table, leaning on your left arm, with your feet behind. Your right arm would then be used to eat the food. This arrangement not only matches Jewish and Palestinian custom at this time, but also makes sense of the idea of John (assuming it was John) leaning on Jesus’ bosom. https://interestingliterature.com/2021/06/bible-jesus-last-supper-summary-analysis/

|

|

|